By Leigh Carroll, Bridget Kelly, Paul Jarris, Will Rosenzweig, and Derek Yach

Much evidence exists on the potential for prevention and health promotion to decrease the burden of chronic diseases. The Institute of Medicine (IOM), for example, has issued many reports with recommendations to use population-based and individual prevention programs and policy and legal interventions to improve diets, increase physical activity, and stop tobacco use.

These reports also note that achieving progress in health promotion will require the engagement of other non-health sectors. This isnt breaking newsterms like multisectoral or health in all policies prevail in public health dialogue. Yet the question remains if it is so well accepted that the health sector alone cannot improve health, why dont multisectoral programs and policies happen more often and more successfully?

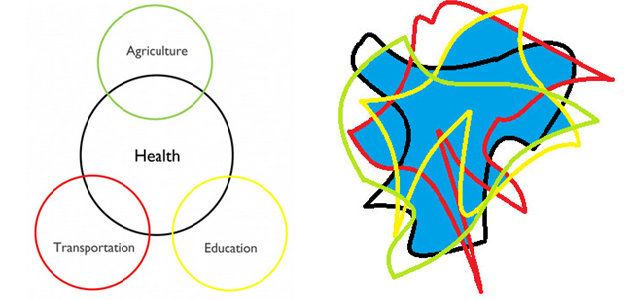

Redrawing What Multisector Looks Like

When the public health sector talks about engaging multiple sectors to improve health, we often envision something like a Venn diagram of neatly overlapping spheres of influence with health in the center. But reality looks a lot more like [the image below on the right.]

Image credit: IOM. Click to enlarge.

Each sector itself is not a well-defined circle, and health isnt conveniently at the center relative to other sectors. In reality, sectors overlap in complicated ways, and there really is no center. There is actually much more interconnectedness the blue area of overlap than a simplified Venn diagram captures. This means that there is a lot of room for sectors to interfere with each others goals if we arent careful, but it also means that there are more opportunities for mutually beneficial collaboration than we might otherwise have envisioned.

When any sector puts themselves at the center, harm can result. For example, health has often been sacrificed when the goals of other sectors take precedence. Take the following examples: Economic drivers support a tobacco industry that has dire consequences for health. Government investments in transportation focus disproportionately on roads and neglect efforts to promote active daily mobility. Physical education classes are cut in education reforms. Government incentives and regulations in agriculture lead to food production that fails to align with recommendations for healthy food intake. Even in sectors within health, resources are often directed away from prevention and into clinical health systems and biomedical interventions. […]

[To read the full article, click here.]